June 1990, the 1932-built Wairakei II leaves Dover headed to Dunkirk for the 50th anniversary of the WWII event.

The movie Dunkirk opened last week and instantly became a box office hit.

It’s by no means the first movie dedicated to the British Expeditionary Force’s evacuation from Northern France in June 1940 but it’s certainly the most colossal ever made.

I actually have a personal connection with Dunkirk and it’s through a boat.

When I lived in the UK at the end of the Eighties, I bought an old 52-foot motoryacht—the Wairakei II—that had taken part in the Dunkirk epic.

The Scottish-built Wairakei II was in sound shape but needed tons of cosmetic work. Among the horrors perpetrated on such a classic yacht was a stainless-steel bow pulpit, which replaced the original cast-iron anchor davit that some previous owner had simply scrapped. Likewise, the two dinghy davits were gone and, in lieu of the required mahogany dinghy, there was a sorry, half-deflated, sun-bleached rubber boat lying on deck.

I scoured the boat-breaker yards in Portsmouth until I found an anchor davit and two dinghy davits that would fit and looked like the originals. I also bought a 1940s mahogany dinghy to carry on deck.

It took me six months to bring the boat back to her original splendor, six months of scraping, buffing, lacquering and repainting. At the time, I hadn’t realized what I was getting into and what it would eventually cost, but it’s been an exciting project even though it nearly bankrupted me.

My self-inflicted ordeal ended in early June 1990, when the Wairakei II—together with 70-odd boats that had also taken part in the evacuation—sailed back across the English Channel for the fiftieth anniversary of the historic event.

On the day of the crossing, the weather was fine but the sea pretty choppy. Many of the old boats had trouble managing an average speed of 5 knots and the Royal Navy had one heck of a time escorting us across one of the world’s busiest shipping lanes. “Like walking a bunch of pedestrians across the M25”, said a Navy officer.

It took us the best part of the day to cover less than 50 nautical miles and the had already set when we entered the lock leading to the Dunkirk inner harbor. Hundreds of people lined the quays in the blustery evening and there were even Breton bagpipes welcoming us in.

A year later, I moved to Brussels and took the Wairakei II with me and moored her at the BRYC (Brussels Royal Yacht Club). In 1992, when I moved back to Italy, I sailed the boat through the Belgian and French canal network to the Mediterranean.

A year later, I moved to Brussels and took the Wairakei II with me and moored her at the BRYC (Brussels Royal Yacht Club). In 1992, when I moved back to Italy, I sailed the boat through the Belgian and French canal network to the Mediterranean.

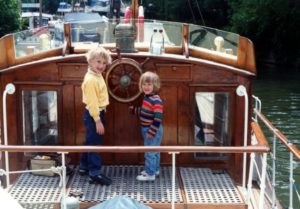

I can actually boast having sailed a boat to elevation 1300 feet, which is the highest altitude reachable through the lock system of the French Canal de l’Est. (The photo on the left shows my children, Rob and Laura, on the Wairakei II’s flying bridge in Weybridge, Surrey.)

I eventually entered the Mediterranean at Le Grau du Roi, in the Camargue and it was a warm summer day when the Wairakei II become acquainted with real waves once again.

Back to Dunkirk, the movie.

I hoped for a moment my old boat (which I eventually sold in 1993) would be featured in the film, but they apparently picked another yacht (they christened it Moonstone in the movie), which in real life is the Revlis. Curiosly, the real 1939-built Revlis did not take part in the Dunkirk evacuation but came from the same Scottish boatyard that built my old Wairakei II, James A. Silver of Rosneath.

The last time I walked on the Wairakei II‘s deck was in 1993, when I showed her to a young British shipwright who eventually bought her. But I’ve never stopped loving that majestic old lady and the very mention of the name ‘Dunkirk’ still sets my heart aflutter.